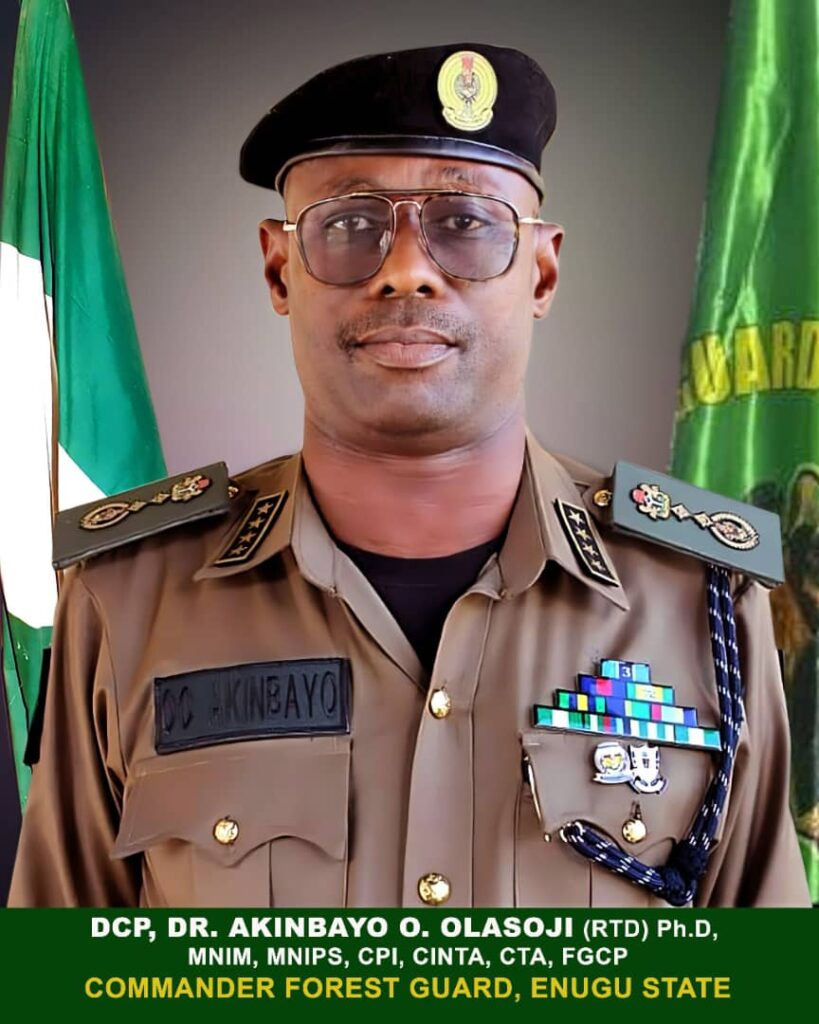

Lessons from the lectures delivered by the Enugu Forest Guards Commander, Dr. Akinbayo O. Olasoji at the National Training for Forest Guards in Osun State

Across Nigeria’s vast forest belts, ungoverned spaces have increasingly become theatres for violent crime, farmer–herder conflicts, illegal grazing, banditry, arms movement, and environmental crimes. These forests are not isolated wildernesses; they are living corridors linking farms, rural settlements, trade routes, sacred sites, and border communities.

As conventional security agencies face mounting pressure, Forest Guards are emerging as a critical but often under-examined layer of Nigeria’s internal security architecture, tasked with early warning, terrain control, community intelligence, and conflict prevention in spaces where insecurity often incubates unseen.Forest Guards operate closest to these fault lines.

Their effectiveness, however, depends less on force and more on legitimacy. As was repeatedly emphasised at a recent national training in Osun State, forest security succeeds only when authority is exercised lawfully, professionally, and with the consent of the communities that live and work around forest spaces. Without this foundation, security operations risk collapsing into resistance, intelligence failure, and avoidable violence.

It was against this backdrop that the National Forest Guard Training Camp (“Forest Camp”) in Ila-Orangun, Osun State, hosted a set of strategic lectures in January 2026 aimed at redefining how forest security should be practiced in Nigeria.

The sessions brought together recruits, rank-and-file operatives, and ward and sector formations from across the country to interrogate a central operational question: how can Forest Guards enforce the law effectively without becoming a source of fear in already vulnerable rural spaces?

The answer, according to the training, lies in a unified doctrine that places lawful authority, disciplined conduct, and community legitimacy at the heart of forest operations.

Delivered in an intensive 2–3 hour integrated format combining classroom instruction, guided discussion, and field-based application, the lectures focused on Ethics and Professional Conduct in Forest Security Operations and Community Engagement, Conflict Resolution, and Trust-Building in Contemporary Forest Policing.

Ethics as Law, Not Preference

Delivering the lectures, the Commander of the Enugu State Forest Guard (ESFG), Dr. Akinbayo O. Olasoji, Deputy Commissioner of Police (Rtd.), framed ethics as a legal obligation rather than a personal choice. He stressed that forest security authority is derived entirely from law and governance frameworks, not from uniforms, weapons, or discretion.

“Ethics in forest security is not a personal value judgment or discretionary behaviour,” he told participants. “It is a binding statutory obligation.”

He anchored this position in existing legal instruments guiding Forest Guard operations, including the Enugu State Forest Guard Law, 2020, the 1999 Constitution (as amended), the Enugu State Prohibition of Open Grazing and Regulation of Cattle Ranching Law, 2021, the Firearms Act, the Administration of Criminal Justice Act, and the Evidence Act, 2011, alongside public service rules and recognised law-enforcement ethics standards. Reinforcing a core operational doctrine of the ESFG, he declared: “Authority exists only within the law.”

BUILDING SECURITY THROUGH TRUST, NOT FEAR

Beyond legality, the lectures placed strong emphasis on community legitimacy as the foundation of effective forest security. Dr. Olasoji reminded operatives that forests are not empty spaces, but environments connected to daily human activity and livelihoods.

“Forests are not isolated zones,” he explained. “They are linked to farms, settlements, markets, footpaths, and sacred sites. That reality makes community partnership a decisive operational factor.”

According to him, the consequences of poor community engagement are immediate and severe. He warned that mistrust leads to intelligence breakdowns, delayed early warning, increased hostility toward operatives, and the escalation of minor disputes into violent confrontations, outcomes that ultimately endanger officers themselves.In contrast, he argued, trust transforms communities into security partners.

As he put it: “Community engagement is not weakness; it is operational strength. Trust is a force multiplier. When you win the community, you win the forest.”

NON-NEGOTIABLE STANDARDS OF CONDUCT

The sessions translated ethical principles into concrete operational standards applicable to patrols, checkpoints, arrest support, intelligence handling, and inter-agency cooperation. Participants were reminded that public confidence and mission success rise or fall with officer conduct.

Among the non-negotiable standards reinforced were universal human-rights compliance, lawful and proportionate use of force, zero tolerance for torture, brutality, corruption, extortion, or record falsification, strict confidentiality of operational information and informant protection, and political neutrality.

Human-rights compliance, Dr. Olasoji stressed, “applies to everyone, always,” while the use of force must satisfy “lawfulness, necessity, and proportionality.”

Mandatory reporting of misconduct, supported by whistle-protection safeguards, was also emphasised as an institutional duty rather than an individual risk.

DECISION-MAKING UNDER PRESSURE

To strengthen field judgment, the lectures adopted a practical ethical decision model consistent with international enforcement doctrine: L-N-P-A — Legality, Necessity, Proportionality, Accountability.

Operatives were trained to ask four questions before acting: Is it lawful? Is it genuinely required? Is it the minimum reasonable response? Can it be defended openly, in writing, and before lawful authority? The guiding rule, as repeatedly emphasised, was uncompromising:“If you cannot defend it, don’t do it.”

EARLY WARNING AND CONFLICT PREVENTION

A major focus of the engagement lecture was early warning and early response. Participants were trained to identify indicators such as rumour patterns, unusual movement along forest corridors, resource-pressure signals linked to farmer–herder tensions, and enforcement-related triggers capable of igniting rapid conflict.

Forest Guards, Dr. Olasoji explained, are not merely enforcers but stabilisers. “Forest Guards are peace managers,” he noted, “but they must operate strictly within legal limits.”

A standard dispute-management workflow was reinforced: Assess, Stabilise, Separate, Dialogue, Decide (Enforce or Refer), Document, Report, and Follow-up, with clear thresholds for referral to the Police, DSS, courts, and civil authorities.

HIGH-SENSITIVITY ENFORCEMENT:

OPEN GRAZING

Given the sensitivity of open-grazing enforcement nationwide, the lectures stressed that operations must remain calm, law-based, non-discriminatory, and free of harassment, extortion, ethnic profiling, or improper impoundment. Ethical professionalism, participants were told, is central to preventing rural instability and escalation in mixed-use forest zones.

TRAINING, ACCOUNTABILITY, AND INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSIBILITY

The sessions employed scenario-based learning, decision drills, and misconduct case studies to ensure practical understanding. Ethics and community-engagement competence were presented as mandatory core requirements, forming part of refresher training and promotion criteria, with completion formally recorded in personnel files.

Responsibility for trust-building was distributed across the command structure, from state and zonal commands to sector, ward, and frontline formations, embedding accountability into institutional culture.

A BROADER NATIONAL LESSON

In one of the most quoted moments of the lectures, Dr. Olasoji told participants:“A Forest Guard is a trust-bearer, not a power-holder. Uniform and equipment do not create authority; character does. Without integrity, authority collapses.”

Security analysts say the Ila-Orangun engagement underscores a broader national lesson: that sustainable forest security in Nigeria depends less on coercion and more on professionalism, legality, and partnership with communities.

As Nigeria continues to grapple with insecurity across rural and forested regions, the lessons from Ila-Orangun point to a clear conclusion—when Forest Guards operate within the law and with the people, forests shift from being security liabilities to strategic assets in national security management.